This is the sixth part of a series highlighting the development of a Map Editor app for a game. In the previous posts, we looked at the data model that drives the map editor, and how we are generating C++ code automatically using python scripts. As promised, this part will be all about the entities of the Cocoa application.

Scripting languages are so freakin’ useful. I just had take that out of my chest. There were tons of times where I really wanted to write a small program that would make my life a little easier, but the pain of writing it would exceed its usefulness. I remember that one time when I wanted to know when a webpage on a very old site is updated, and wrote a full fledged MacOS Cocoa status bar app just to monitor the status… It was a pain, and certainly not worth the time. However, now that I learned python over the course of the last few months, this task would take at most 1 minute to code, and would definitely be worth it! from introduction import end.

If I were to ask any programmer on the face of the earth what he would expect the entity classes for this Map Editor app would be, they would definitely say MapMeta class, MapAction class, … etc. It makes sense to assume that, since these are the basic entities of the map, right? Well, it would be correct if this was your typical software that you write everyday, but it isn’t. We explained that this map editor should have these entities defined in a plist, and controlled from there, hence being data-driven. So, writing any code that is tailored to those entities is a no no. So, what to do?!

I will go ahead and say that, initially, I loaded those plist files into NSDictionaries and NSArrays, and the app worked fine. With the power of Key-Value Coding (KVC), which is behind Cocoa bindings, I was able to implement a very generic data model without a single subclass. That is almost impossible to do without making the code horrible unreadable, but fortunately, I utilized ObjC’s categories to work around that! So, no subclasses, just categories :D.

So, did I just stick with this? Unfortunately, the answer is NO. A HUGE burden, believe it or not, was backwards-compatibility. Just by using these vanilla data structures, it was extremely hard to add a proper “version control” thing. This is simply because when you load a plist/json, you typically load the whole thing using a few lines of code, and get a root object. You would either have to traverse it and sort the old version mess somehow, or write your own parser… Not an approach I would prefer. So, let’s just see how it was ultimately done! (Another small problem was that KVC is used heavily to bind the data with the UI. Since these data structures are “highly decoupling” (you access them through keys and indexes, not concrete properties), it makes things hard to debug and write safely)

If we can’t create explicit subclasses, nor use generic data structures, then what’s the compromise we are looking for? I’ll tell you what it is: It’s an “adapter” class that represents a UI element, but has a reference to the actual data! Let us start visualizing what’s going on:

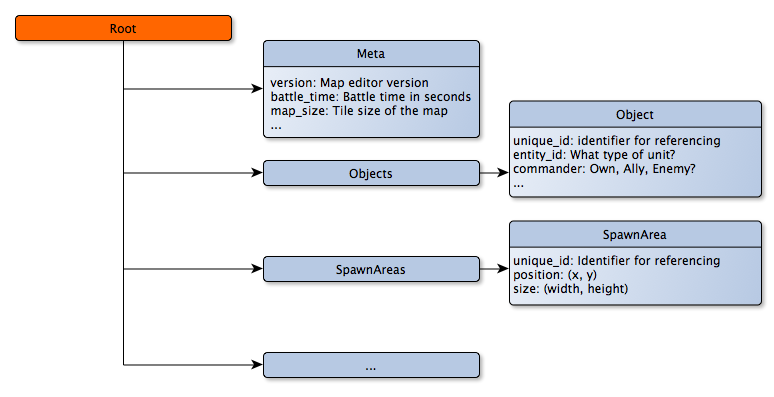

The data models:

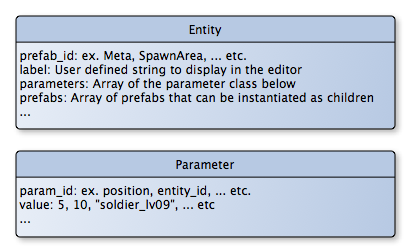

The Adapter classes:

That’s it! Two adapter classes is all we need, really. One class is for the entities that are shown in the top left outline view, and the other is for the parameters that are shown in the bottom left outline view. I don’t think there is anything else to it, honestly. The only interesting part in this would be the serialization, then again, it’s a totally different story…

Conclusion:

I’ll go ahead and admit that I probably didn’t give this series my all, especially this last part. Explaining the data side is always tricky, I guess, even more so when you are doing some weird data wizardly and shtuff. Well, I think I am more excited about what’s coming next, so let’s brush this under the rug!