Introduction

With the rise of chat bots, concurrent programming, and elixir, I thought I might as well shed some light on the elixir bots server I wrote for my own needs.

The reason I wrote a bots server was mainly because I found it difficult to test my game’s online capabilities on my own. When I go the game rooms, there are no rooms, since there are no players yet! Also, not enough online events are being triggered, such as leaderboard changes and what not..

So, in order to test my game client, as well as provide a rough integration testing mechanism, I decided to write this bot server.

I Am Bot

The bot server is a simple Elixir application that has 20 bots sitting directly in the main supervision tree. Using a one_to_one strategy, the bots will recover after a crash, and life goes on.

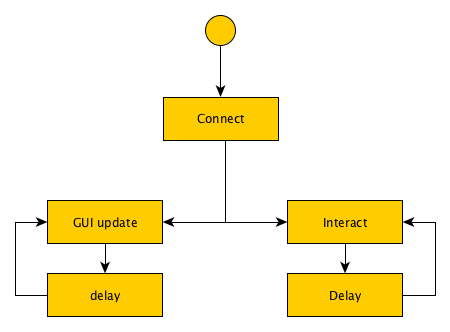

A bot process is basically this:

Just an infinite loop that updates the GUI with the latest state and messages, and another loop that triggers the “interact” action. The really interesting part is the interaction, so let’s take a closer look at that.

Machine With Finite States

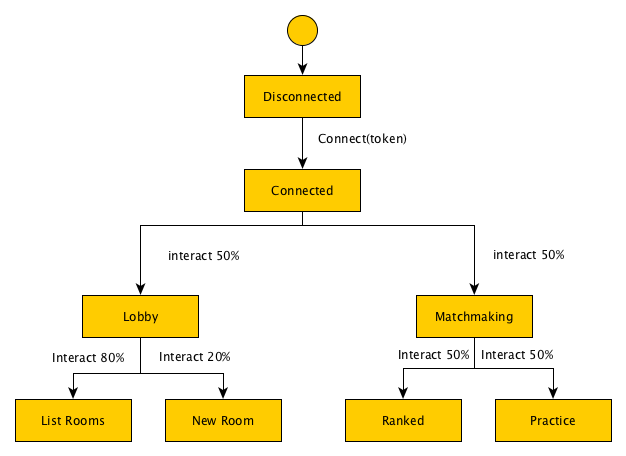

I am using the neat FSM library to create an FSM that the “bot state” uses to manage the logic. The “bot state” is just an FSM stored in the bot process, and works something like this:

So, after connecting to the server, whenever we send the FSM an “interact” event, it simply runs some logic to figure out what the next state should be. The available options are also weighted in such a way that we control the chances of the bot choosing one path over the other. This is extremely important, since for example, once the bot enters matchmaking, we give it a 5% chance to give up and leave the matchmaking queue. This is to ensure we test all possible actions!

If we were to look at some of the fsm code, it looks something like this:

### MATCHMAKING

defstate matchmaking do

## Interact

defevent interact, data: data do

action = Enum.random(List.duplicate(:wait, 24) ++ [:leave])

case action do

:wait ->

GUI.update_message :gui, "Matchmaking ..."

WS.send_heartbeat data.sock

next_state(:matchmaking)

:leave ->

GUI.update_message :gui, "sick of mm waiting!"

WS.leave data.sock, data.channel

next_state(:connected, Map.delete(data, :channel))

end

end

## Opponent found

defevent on_reply(event, %{"id" => id}), data: data do

GUI.update_message :gui, "[#{event}]: #{String.slice(id, 0..7)}"

WS.leave data.sock, data.channel

channel = "matchmaking:" <> id

WS.join data.sock, channel, %{}

next_state(:mm_session, %{data | channel: channel})

end

end

The code above represents the “matchmaking” state. So, the bot has entered a matchmaking queue, and is waiting for an opponent. While waiting, each time we call “interact”, we either continue waiting, or give up and leave. Chances are 24:1 as you can see above.

As for the defevent, this simply handles the server message if an opponent is found. The way this works is, the bot process simply forwards all incoming server messages to the bot state using the on_reply event. We use pattern matching to extract the id of the matchmaking session, then move on the mm_session state!

Closing Remarks

That’s all there is to it, really. I have to say, this server was more than worth writing. It helped my test the client app easily, as well as find bugs and issues on the server side.

For example, I run 20 bots at once and they all play and interact on the game server. After integrating the game logic on the server, I found that the game logic process hangs in certain rare cases! I would have never caught that by testing manually on a Unity client. Also, the game logic is a python process, so when it hangs, it really breaks the whole server! That’s terrible, but thankfully, resolved.

Also, I can easily do load testing by running 1000 bots or so on one machine and closely monitor the server’s performance. I am not worried about performance at all in this case, since it’s a turn-based game, but it’s easy to do, so I’d probably do it just for the heck of it.

Conclusion

Elixir is just great for writing bots, whether they are chat bots, testing sentinels, or whatever. The Actor-based model maps to bots 1-to-1, so that should really be a surprise!