Introduction

Alrighty then, it’s time for the second part of this HTTP game server awesomeness! In case you missed it, you can check out the first part over here.

For this part, I’ll present the technical decision made, and the reasoning behind them.

Why HTTP?

I completely forgot to justify using an HTTP server instead of a socket based server!

First, let’s quickly learn what a socket based server is..

Socket Server

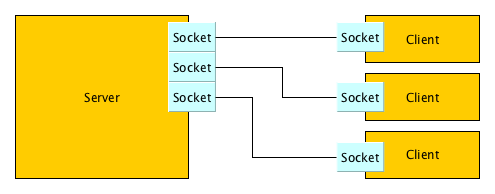

A socket based server is basically a server that creates a communication socket for each connected client. This socket is basically “the doorman” for a persistent network connection (either TCP or UDP) that the server and client start communicating through:

The biggest advantage here is that the server can push data to the client at anytime, without the client specifically requesting something. This can be useful for multiplayer games, where the actions of a player are broadcasted to all the connected clients.

The biggest disadvantage, however, is the overhead introduced by these sockets. Each sockets takes up a considerable amount of memory, and moreover, there is a physical limitation on the number of connected clients you can have. This number is usually regarded as CCU (concurrent users).

The Answer

From the previous points, we can see that since our game is turn-based, without much interactivity, we can easily overlook the latency overhead introduced by an HTTP server, and in return, be able to serve potentially thousands of CCUs without any hassle at all.

Why Google App Engine?

I honestly don’t have a really good answer to this, since other solutions might work just as well … But, there are definitely at least a few really appealing things to GAE.

The speed at which you can publish a web app on GAE is just freakingishly fast. The database and memory cache are setup for you, and all you really have to do is focus on writing your application. That alone is freakin genius to a frontend developer like me, since I don’t want to bother with that crap.

Then, comes the benefits of trusting GAE with all these details. Since you don’t handle the configuration, GAE manages that for you and can scale automatically with zero intervention from your side. It also has its own analytics dashboard with almost everything you might hope for:

- Exceptions: Errors raised in your app

- Client Errors: 4xx responses

- Logs: Very neat logs view, with severity

- Stats: CPU usage, datastore, memcache, … etc.

Of course, with all this comes the downfall: It’s not easy to migrate away from GAE once you are invested. Also, the restrictions the platform imposes on your code is not to be taken lightly. You have to be mindful about how you write your code, and even how you design your model’s classes and relationships.

The biggest drawback I’ve read online of GAE is the cost, especially if you are drawing intelligence from the data you have. Wait, what?

Well, once you’re application is running, you will start filling you database with crap, and then you might want to have a tool that reads that crap, processes it, and presents you with some intelligence? That access alone is costly, since you are attempting many, many read operations, especially with a large user-base.

There is a way around that restriction, and that is to setup RPCs to another server, that “replicates” the data store, and you can mine that instead. But, whatever happened to focusing on writing your app?

Conclusion

Sorry about all the theoretical part, but these early technical decisions are just as important as any part of the process, and I though giving insight on why things turned out the way they are will be useful for the lot.

Hopefully, the next part will more technical and about implementing specific game features on the serve.

Hang around!