This is the second post of a five part series where I explore the most famous software design patterns and try and give an overview with examples from my own perspective. If you haven’t, check out the first part of this series, which is also about behavioral design patterns.

When I think back to my software engineering class, I remember the professor asking two simple questions right of the bat, and no one was able to give a clear and precise answer. What does Design mean? What does Analysis mean? Such simple questions with very deep meanings. OK, so from my terrible memory, I recall that Analysis is deep understanding and research of a particular subject, while design means… I have no idea, totaly slipped my mind. According to wikipedia, it basically means the plan or strategic approach to a achieve something. Well, I have to say this is probably the first useful and meaningful introduction of all my posts… Onto the post!

I would first like to note that I have found this amazing website that explains design patterns 1000 times better than what I am doing here, which leaves me disheartened, but I need to finish what I started! I was trying to beat wikipedia, but this website is just awesome. Check it out.

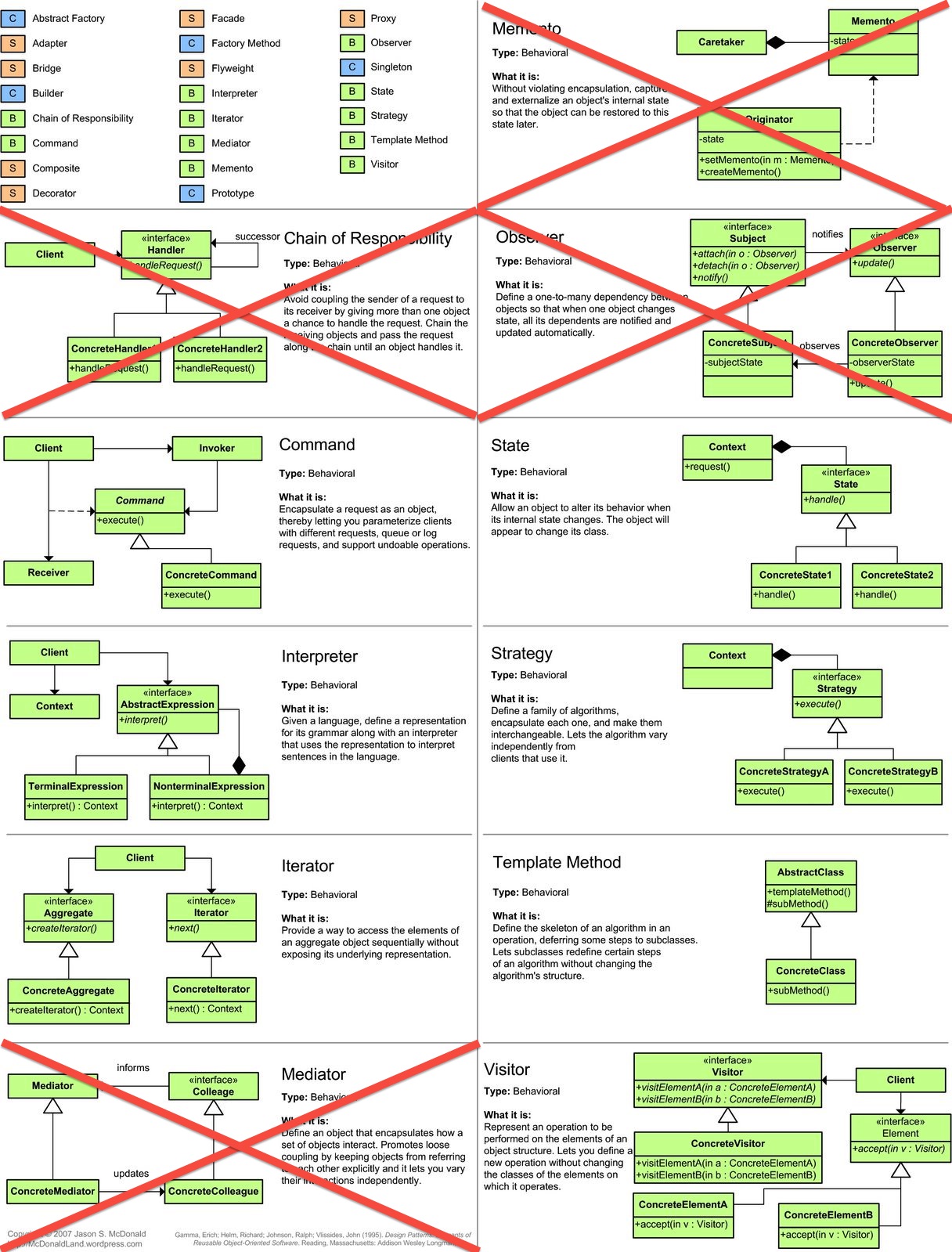

Let us take a look at the list again, and see what we have left from the behavioral patterns:

OK, I know what you are saying. There is some asymmetry. The previous part contains less than what is left. Well, that is true, however, there are actually two patterns that I am not even going to bother cover, and two patterns are almost identical, so it should add up evenly.

Command

Use case: ★★★★

Elegance: ★★★★★

Overview

In order to decouple a sender and receiver, the command design pattern can be used as solution to the problem. As always, you have a class that is like the mastermind that knows what needs to be done, and a zoo of objects that it can access, but they need to be decoupled. So, let’s see how the mastermind would do this: “Hey, you object over there, yeah you. You are dealing with all the network related stuff, right? Do me a favor, will ya, here is a command object, DO NOT LOOK INSIDE! Whenever a packet is received, just invoke the execute on that object, and give it the payload.”. So, what did the mastermind give the network object? Probably a command object that has two important things: 1 - a pointer to the packet handler, and 2 - the method to be invoked on that object. Note though, that the pointer would probably be private, and hence completely encapsulated and unknown to the network object.

Example:

I think I am mixing the examples with the overview, honestly. It is so hard to explain these patterns without an example… So, the example can be read in the overview, you have a controller object which has a pointer to a network object and a packet handler object, and it does the magic explained above.

Interpreter

Use case: ★★★★★

Elegance: ★★★★★

Overview

The interpreter class… I love this design so much, just because I actually used it without reading about it, so let me rant a little bit about it. We had a course in college called “Numerical Methods”, and the project for that course was to write a program that can solve an equation system, or whatever it was called, with a number of available methods. The equations should be entered by the user. I realized that I have two serious problems here. The first, is that I have to define a very clear format for the equation to be written by the user, so I can parse it easily. I wonder if there is a design pattern suitable for that. The other problem is the functions available for the user to put in the equation. I need to be able to add a new function after I am done with the core code easily. For example, initially I just added the “variable” function (f(x) = x), and the sin function (f(x) = sin(x)). When I was writing that, it became clear that they are exactly the same from a high level perspective. They all take a single input, and produce a result. Hence, leading me to the creation of a general interface (I think I called it Equation), which all these sub-functions implement. So… With these classes written, all I have to write is some sort of parser or interpreter that instantiates these sub-equations as it parses the input of the user. It is so elegant, since the Equation subclass takes another equation as a parameter, hence you end up with nested awesomeness: SinEquation(CosEquation(NumEquation(4))); The number equation class is an exception, probably, it just takes a number, and returns it as the equation value. So what would happen here is, I would call “evaluate” on the SinEquation, which needs the value of the CosEquation, so it called “evaluate” on that, which needs the value of the NumEquation, so it calls “evaluate” on that, and the NumEquation just returns the number.

Phew! So, it is a pretty awesome pattern, and the use case is for real. The great part of it, is the ability to just add new “grammar” to the interpreter as a new isolated subclass whenever you like.

Example:

The example was the mathematical equations, actually. They have a pretty standard syntax, but they are complex because they can be nested and whatnot. All we have to do, is identify what an equation is on a small building-block scale, and bam. We have our interpreter design.

Visitor

Use case: ★★★★

Elegance: ★★★

Overview

Yet another popular, yet not so elegant design, since apparently, it ties itself to the data structure of the object hierarchy. The visitor pattern’s main point that I would like to highlight is, “It recovers lost type information.”. The way this pattern works is by having two main classes participating in the design to reach the ultimate goal, which is … “recover lost type information.”.

So, the way this works in a nutshell is, you have an Element abstract class that is taking part in a heterogeneous data structure (let’s say an array, for example.). So, you have an array of element subclasses, since the Element class is abstract, but you want to perform operations based on the concrete type of the Element object in the array! Do a type check? No way! We are better off “recovering lost type information.”. OK, so can we just iterate the array and send these objects to an overloaded method that will know the type at runtime? Not quite, since the object’s implementation might want to control how the operation proceeds based on the type of operation applied! Hence, we introduce … (Drums please…) The Visitor pattern. By writing a Visitor class that overloads several methods each taking a different Concrete element type, and adding the “acceptVisitor(Visitor v)” method, and overloading it, to the Element superclass, we effectively made the the Element subclass decide what to do based on the concrete type of visitor it was passed in the “acceptVisitor(v)”, and will ultimately call inside that method something like: “v.visit(this);”, and if the visit is overloaded in the visitor class, it can handle that object as well. That is what double dispatch is all about, and the fuss about the Visitor pattern.

Example:

Many cool examples pop to mind when thinking about the visitor pattern, especially the typical rendering tree in most game engines. Game engines usually have a base class called “Node”, and that node class is derived into classes, such as Sprite, Text, Color, … etc. These classes handle the renderer differently, so we call the Visitor pattern on board. When you call the acceptVisitor(v) on the top most Node subclass in the render tree, it would iterate over it’s children, call acceptVisitor(v) on them, and then call v.visit(this). Let us assume that the visitor in this case is the renderer, which will render the object. In that renderer, we would have a list of overriden methods for the TextNode, SpriteNode, … etc. that we mentioned. This pattern clicks perfectly with this use case.

MILLION DOLLAR QUESTION: I interviewed with cocos2d-x a month ago, and I had no idea how the visitor pattern works, and they asked my a question that was easily solvable by this pattern, ARRRGHHH!! So, let me pass the knowledge as a question… Don’t you think there is something wrong with this design pattern? Maybe “too deep” than needed?

HINT 1: Only read the hints if you are desperate!! Why should we bother with the “double overloading” thing. Why can’t we just send the visitor to the objects in the hierarchy, and in each object’s acceptVisitor(v) method, we use that v “renderer” to render ourselves in the Node subclass. Sounds like a neat idea?

HINT 2: Actually, there are cases where using the “rendering visitor” in the Node subclass is an extremely valid approach. In fact, ObjC, Java, and I am sure other languages use that in their “simple” renderers. In Java, it is the “paint(Graphics g)” or “paintComponents(Graphics g)”, and in ObjC, it is the “drawInContext:(CGContextRef)ctx” method. These methods are called on the view hierarchy, and the renderer is passed to everyone in order to render themselves as needed. BUT NOT FOR REAL GAME ENGINES, WHY?! ‘nuff said. (Such a delicious interview question)

Strategy

Use case: ★★★★

Elegance: ★★★★★

Overview

When I read about this pattern in a previously mentioned website (I am trying to preserve anonymity here (I am just trying to use a smart word, actually)), the author seemed to have become quite emotional about the purpose of these design patterns in general. It made me realize that this pattern in particular may represent your ideal software pattern. It is quite elegant, if I do say so myself.

The idea is quite simple. You have a very generic interface with input and output, which can be a single method if you want to, and that interface is implemented by as many concrete subclasses as needed, with the only requirement that they implement that method. Then, you would have a set of objects that need to processed according to different strategies. Hence, they only need to “see” the abstracted interface of the of all the strategies, and interact with that. The implementation that happens within these subclasses it completely hidden from the receiver.

Example:

A very straight forward example is a String Formatter. Let’s say you have 10 text inputs presented to the user, and you want to format each box differently. The first box should be formatted as a currency, so if the user enters 10000, it will be displayed as $10,000, and the second input is for a phone number, so it would display as (123)456-7689, and so on… The text input fields don’t need to care about how the formatter will work, they only need to know that a formatter takes a string, and returns a new string that should be update the text field. Thus, a Formatter interface is defined with a “formatString(s)” method that returns a formatted string, and the text field objects check if the formatter ivar inside them is set, they call formatter.formatString(getText()) each time the string change, or when the user hits return. Elegance.

Leftovers

State

It is exactly the same design as the Strategy pattern, except for the intent in both design patterns differ. In the State pattern we are interested in running different code when the same object’s state changes! Take the previous formatter example, we would have a state machine of formatters, and when the user hits right click on the text field, and chooses EU, for the Euro currency, the formatter would detect that the text field’s state changed from dollar to Euros, so it can change it’s formatting strategy accordingly. I know it is a bit vague, but I really think this pattern is a very narrow and special pattern used in very narrow cases which would make sense to use this pattern immediately when confronted with such case.

Iterator

The iterator pattern is honestly lame and mostly implemented by the language and used on-the-fly by the developer. It just tries to hide how the data structure fetches the next object, and checks whether there is another object in line or not. For example, when you instantiate a linked list, and get the iterator, it will first set the itr pointer to the head of the linked list. So, when you call “next()”, it would use the itr to return the object in question, as well as move the itr pointer to the next object by using something like: “itr = itr->link;”. Very basic linked list implementation, however, most likely the object traversing the linked list doesn’t need to know how the heck this works, hence the iterator pattern.

Template Method

This one really fooled me. I thought it was some magical pattern that can literally create a templated method with “slots” that can be changes per subclasses requirements. Alas, thou is nay. It just imposes some “leaky abstraction” by cutting down a certain method contents into a bunch of other method calls that can be overriden by the subclass to do something else. So Laaaaame.

Conclusion

Well, it was certainly fun and tiring exploring all these design patterns. I feel they have really solidified within me, and I should start using them ASAP to find these blind spots that I am not seeing just by talking about these patterns without code. A simple example would be the fact that I mentioned method overloading for the visitor pattern, but ObjC doesn’t have method overloading!! Need not worry, since it has an even more awesome thing that makes method overloading cry. Well, I hope to do an overview on the structural and creational patterns soon, but for now, might as well return to the map editor series! There has been a breakthrough last week!